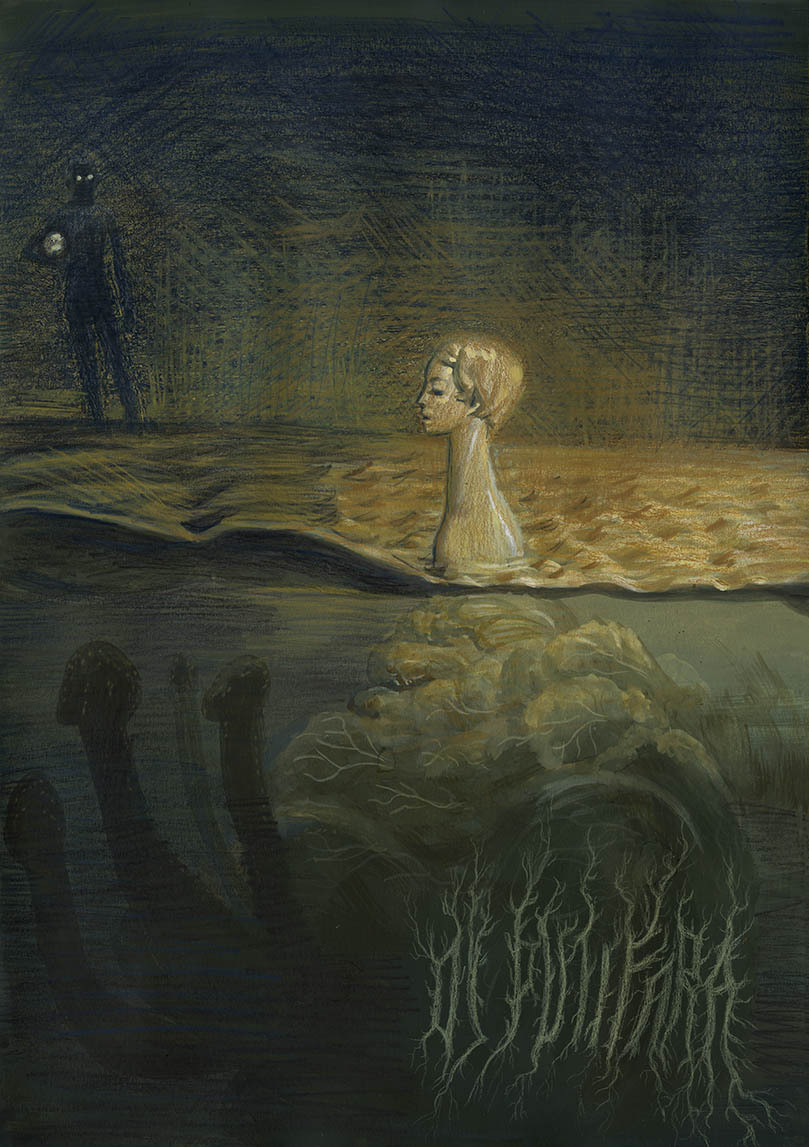

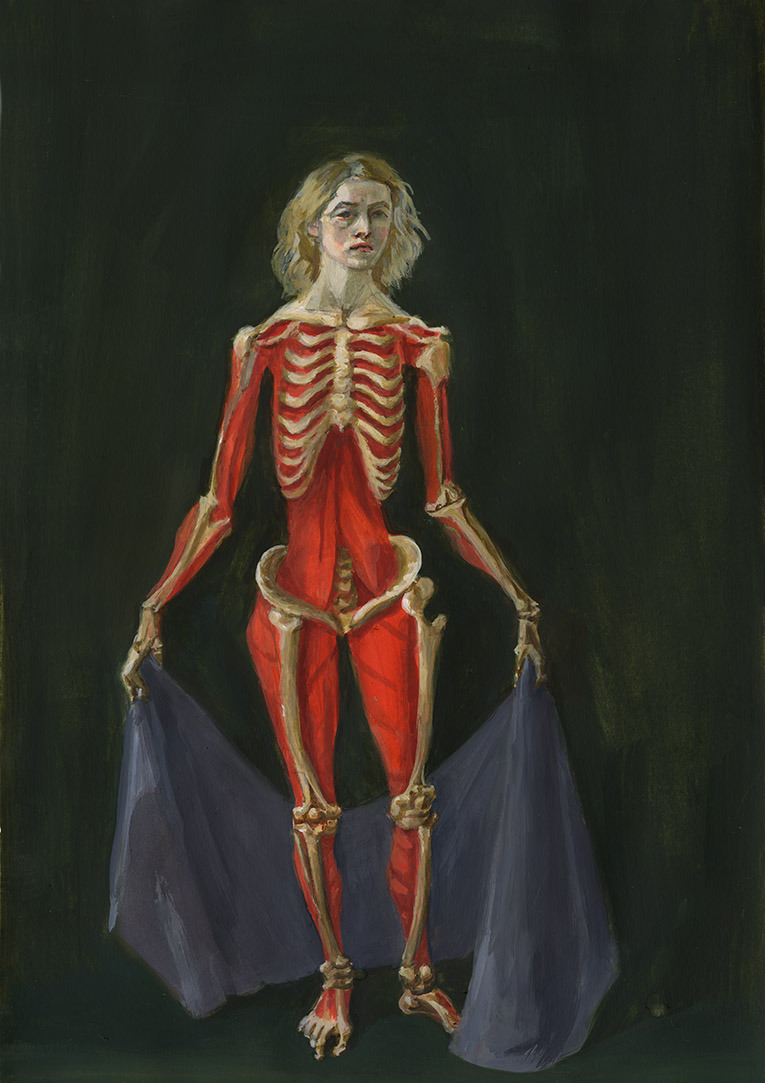

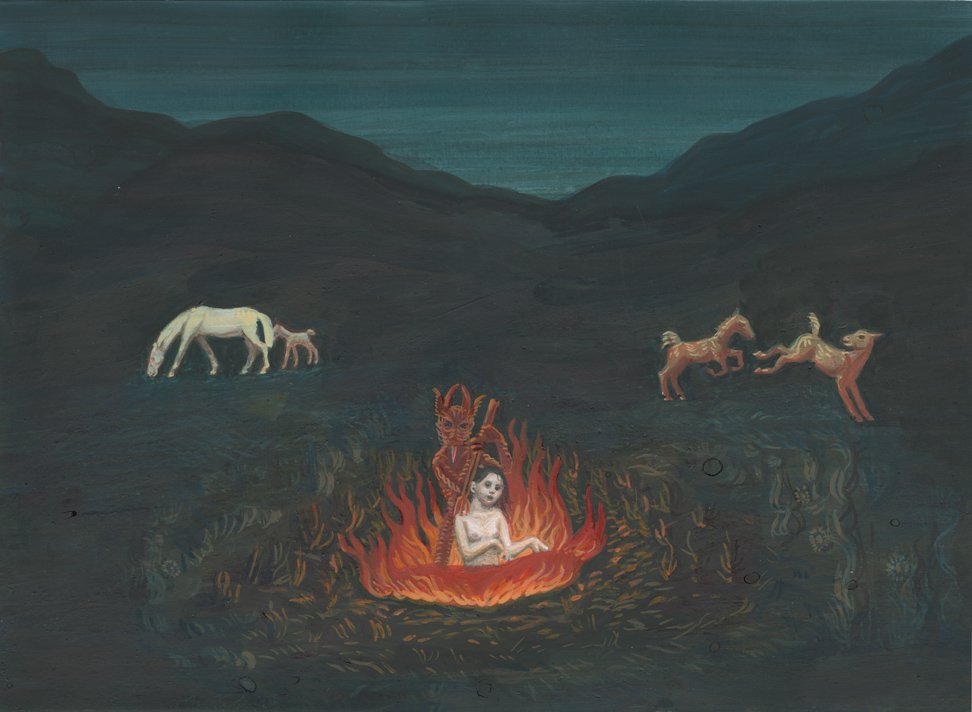

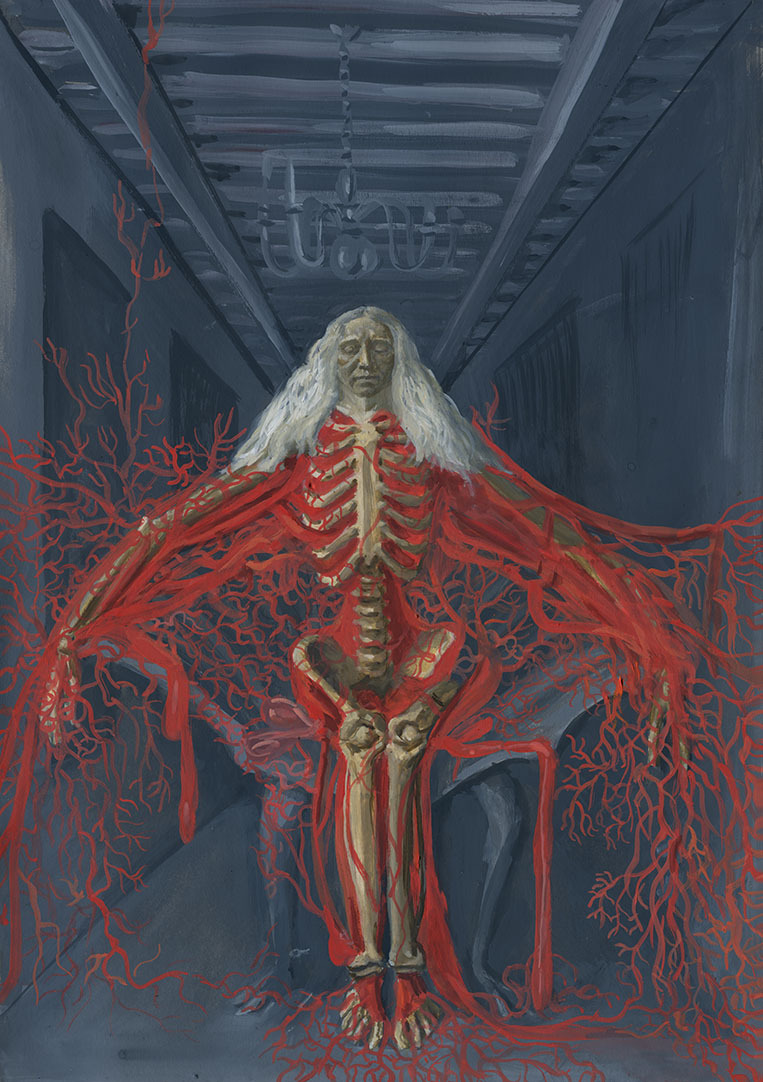

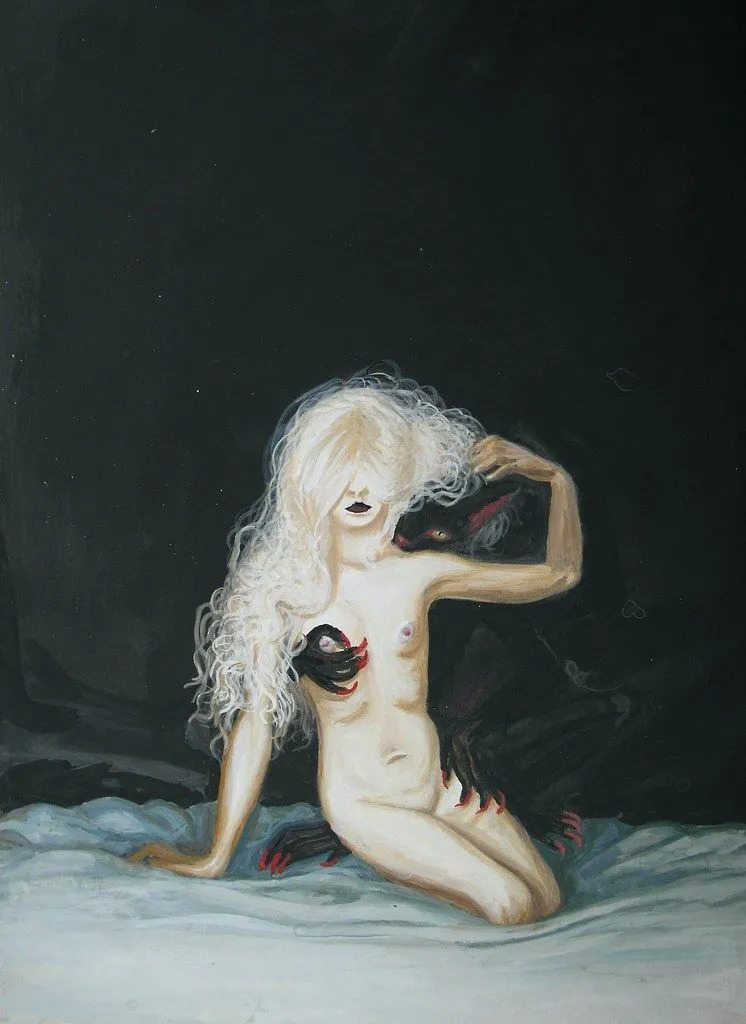

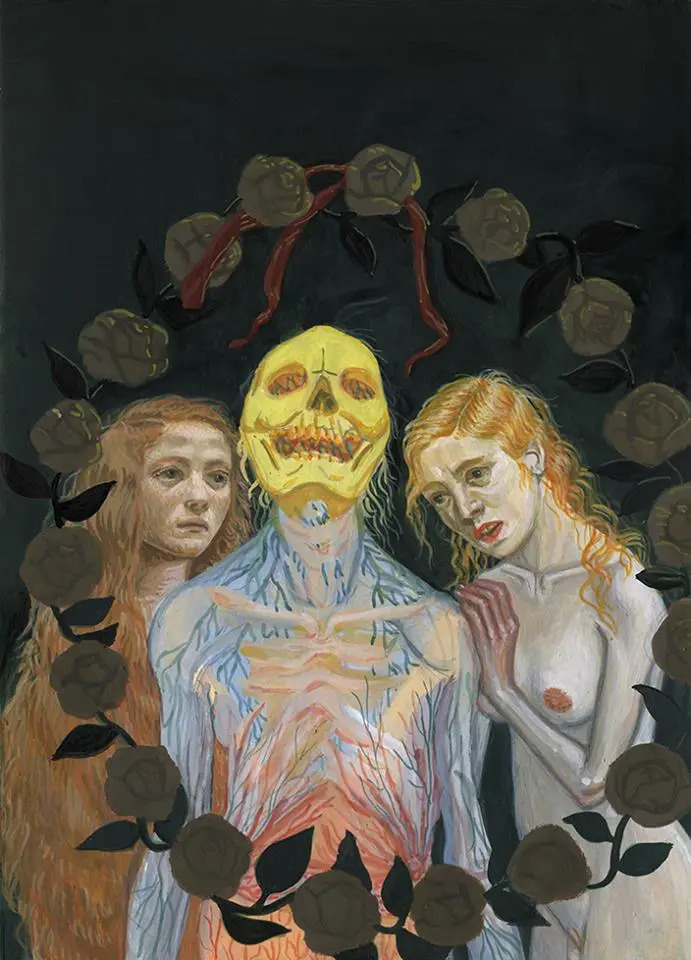

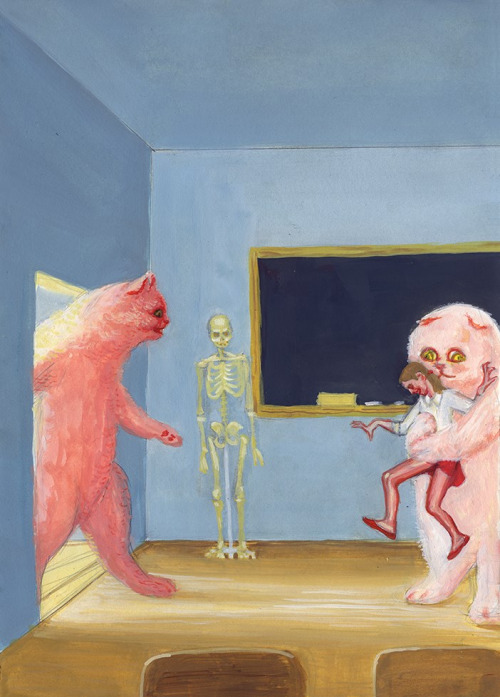

Warsaw-based artist Aleksandra Waliszewska paints the inner landscape of nightmares. With her rather primitive, naive style, her oil and gouache paintings also have an ostensible childlike sweetness which is belied by the horrific themes depicted. She is fascinated by themes of torture, sadomasochism, and the macabre, drawing from a variety of influences including Renaissance art, fairy tales, folklore, and horror movies. Her paintings are often inhabited by young women with an androgynous, waifish physique and uncanny children, alongside monstrous cats, spider-women, and other hybrids of beast and man. These strange beings perpetrate and have perpetrated upon them gruesome acts of violence and violation – the line is often blurred between prey and perpetrator. The subjects, whether victim or villain, tend to possess a malignant or sinisterly mischievous air.

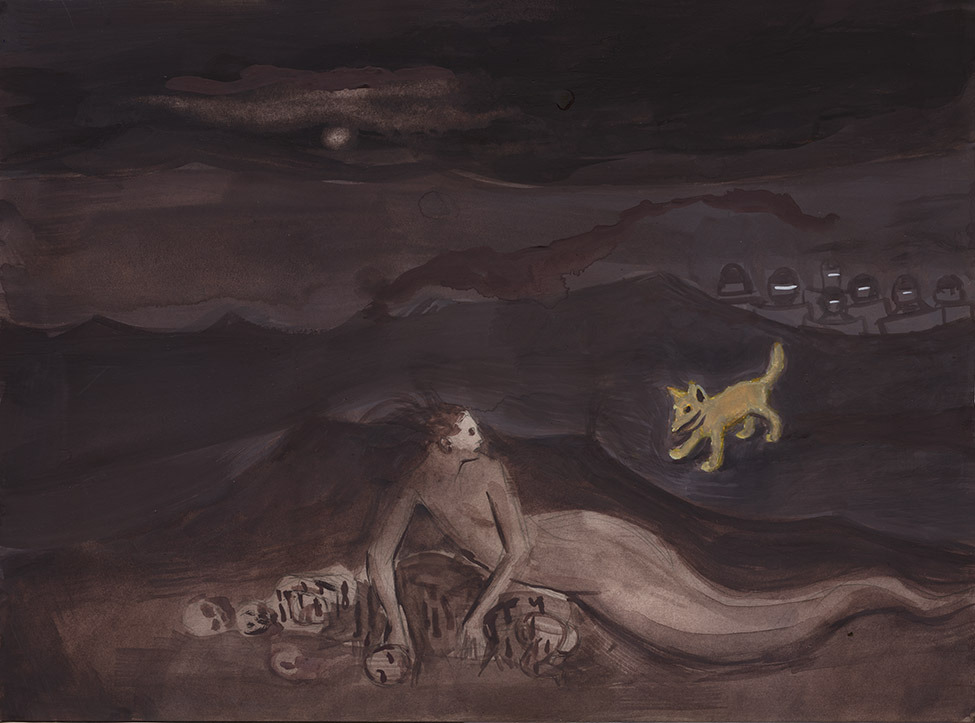

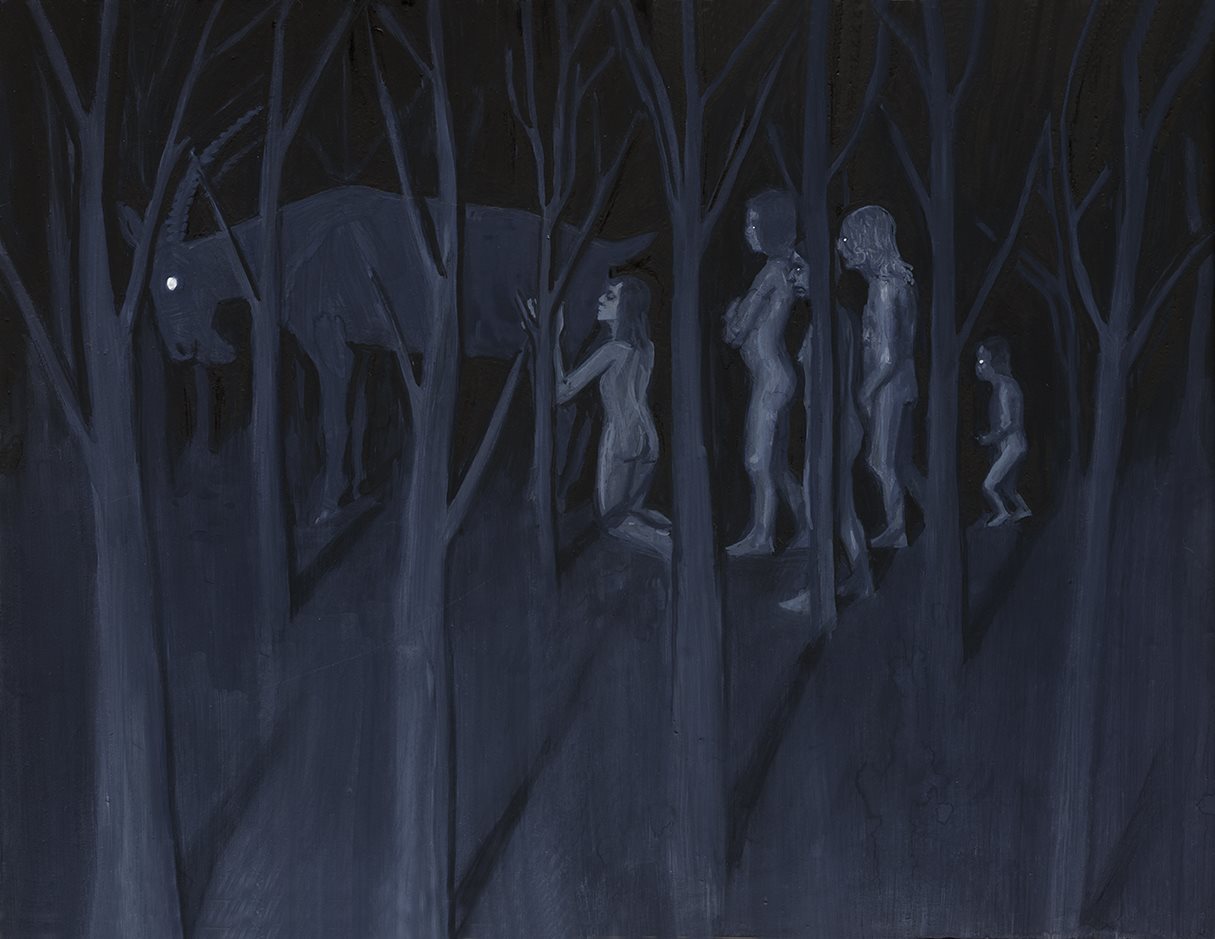

As S. Elizabeth writes on Unquiet Things, “Whether against the backdrop of a well-lit classroom, a shadowy forest landscape, or the viscera-strewn confines of a dusty cave, madness, magic, and mythology cavort hand in bloody hand.” These morbid and perversely jovial scenes take place in eerie wastelands, lonely forests, empty and surreal wildernesses. I find her work to be reminiscent of the classic surrealist painter Leonora Carrington. Waliszewska is more inspired by historical art and the Quattrocento than contemporary movements, although she also takes imagery from modern sources such as video games. The Dark Arts: Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism explains: “Drawing from the specifically Slavic histories of the Upiór (the living dead), Waliszewska claims her artistic and conceptual descendance from premodern art and Symbolist works of the late 19th and early 20th century from Nordic, Baltic, and Eastern European regions.”

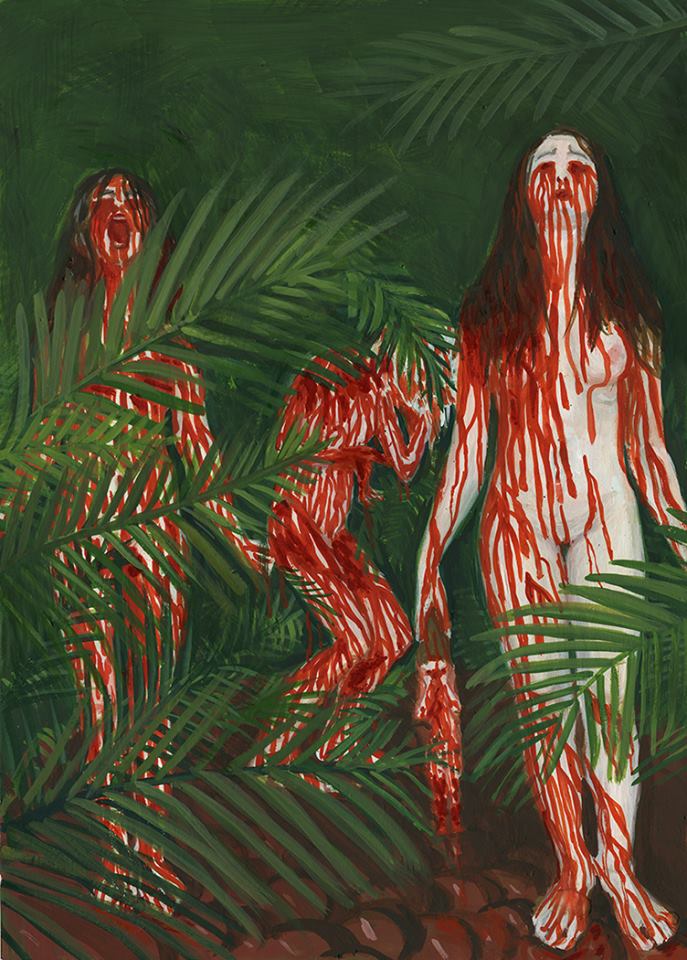

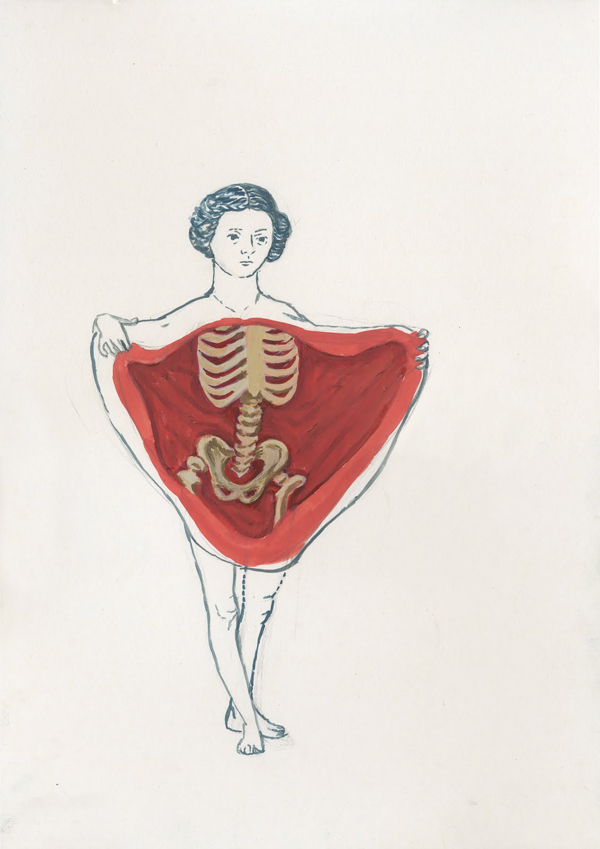

Waliszewska’s dark, supernatural motifs come from a world that is intriguing and disquieting, a world both morally and aesthetically void. Faces have round holes in them through which the underlying anatomy is exposed; women open their skin to the viewer like robes; a pair of terrifyingly red eyes peers through a pink curtain like a wall of flesh; a bodiless head brushes its own hair with a severed hand. Multiple paintings depict groups of girls subjugated and chased like a herd of animals, fleeing through the woods with bleeding cuts all over their bodies, or with their ankle bones broken and protruding through the skin as they run in red high-heeled shoes. There is a sacrificial element to these group tableaux, as if they were enacting a ritual hunt. I love how the red cuts against their pale skin are so numerous that the girls resemble birch trees.

Agnieszka Le Nart describes her paintings as “disturbing [visions], as if taken out of a small girl’s nightmare,” and “perverse fairy-tales where the idyllic games of tiny heroines blend with sophisticated horrors and everything is interwoven with a strong eroticism….These little women can sometimes be victims, but other times they’re the initiators of violence; girlish innocence intertwines with something demonic and repulsive….The paintings include numerous archetypal images that resemble something from a medieval bestiary.” Uncomfortable to look at and focusing on imaginative expression rather than formal perfectionism, Waliszewska’s paintings have the immediacy of nightmares, direct and visceral yet enigmatic.

Aleksandra reaches into some dark subterranean elemental place where all things happen, forbidden and beautiful both.

— Susie Cave

Waliszewska’s art inspired the 2012 short film The Capsule, directed by Athina Rachel Tsangari, which looks utterly intriguing and reminds me of Lucile Hadžihalilović’s 2004 film Innocence. Co-written by Tsangari and Waliszewska herself, the plot description cryptically states: “Seven young women. A mansion perched on a Cycladic rock. A series of lessons on discipline, desire, discovery, and disappearance. A melancholy, inescapable cycle on the brink of womanhood — infinitely.”